Because of the nature of online courses, students and professors may sometimes feel left out or isolated. The issue is that people may feel less connected in an e-learning course because they may never see their peers or the instructor. This is known as the “isolation effect” and has been well documented in the literature. However, live Blackboard Collaborate sessions can go a long way toward helping remote students feel that they are a part of a larger class.

Because of the nature of online courses, students and professors may sometimes feel left out or isolated. The issue is that people may feel less connected in an e-learning course because they may never see their peers or the instructor. This is known as the “isolation effect” and has been well documented in the literature. However, live Blackboard Collaborate sessions can go a long way toward helping remote students feel that they are a part of a larger class.

Professor Weinstock has developed some interesting ways of circumventing the isolation effect, by using Blackboard Collaborate and he wanted to share his instructional strategies for those who may not have used this technology before. Collaborate is a synchronous communications tool much like Skype, but it is used for live online classes. As he describes it, the trick does not lie in the technology itself but, rather, in how the instructor uses the tool. Many a collaborate class has been a dull “talking head” lecture or, even worse, “death by PowerPoint.” however, by implementing several easy techniques, professors can transform what would be just one more tedious webinar into a live engaging class.

Professor Weinstock’s collaborate sessions were once a week, some were optional, and some were mandatory. All were synchronous (meaning that students were strongly encouraged to attend and participate live) but the sessions were also recorded for later playback, in case students were unable to attend. As he described it, the notion that some sessions were mandatory created a sense of urgency and made students really feel they had missed something if they hadn’t attended the class. However, he found that both the mandatory and optional sessions had almost 100% attendance.

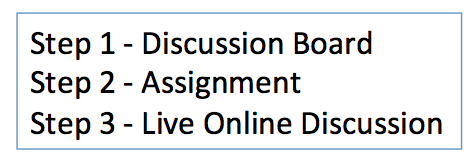

There are several reasons for his success. Professor Weinstock developed a generalizable instructional process that can be replicated to all classes, including classroom-based courses. The process includes three steps: the instructor begins by presenting a topic each week in the online discussion board. This topic is based on the week’s readings in the textbook and is typically a practical application of the topic. Students are required to post their responses on the discussion board as well as commenting on at least two of their classmates’ posts. This creates a sense of community and discussion, instead of the typical binary student-instructor dialogue. At the end of the week, students also submit a longer written assignment on the material. Finally in the following week a Collaborate session covers the topic and serves as a live discussion of the material. This way all students are well versed in the material, having interacted with it several times, and are able to discuss the subject matter in a more engaged manner.

Professor Weinstock described several additional success factors:

Structured sessions: collaborate sessions had a structured agenda, which was based on discussion of specific pre-defined topics; they were not simply office hours. Consequently, students felt that they were participating in an active learning experience. ProfessorWeinstock used a PowerPoint presentation as a visual aid to illustrate his points and stimulate class discussions. For the most part, the PowerPoint presentations were image-heavy and text-light. There is much in the way of documentation that describes the advantages of this type of PowerPoint. He felt that the well-structured, defined agenda was extremely important for guiding the discussion.

Structured sessions: collaborate sessions had a structured agenda, which was based on discussion of specific pre-defined topics; they were not simply office hours. Consequently, students felt that they were participating in an active learning experience. ProfessorWeinstock used a PowerPoint presentation as a visual aid to illustrate his points and stimulate class discussions. For the most part, the PowerPoint presentations were image-heavy and text-light. There is much in the way of documentation that describes the advantages of this type of PowerPoint. He felt that the well-structured, defined agenda was extremely important for guiding the discussion.- Student involvement: students were encouraged to speak up and ask questions and even to instant message one another via the collaborate tool throughout the course, but most certainly in the synchronous sessions. He wanted students to continue this interaction and involvement beyond the live session for the rest of the week.

- Timing: Professor Weinstock used the “4-minute rule.” At least once every four minutes students were required to interact. This could be a “knowledge check” where he asked for a definition or real-life example, a “student poll” where attendees used the collaborate tool to agree/disagree with the topic being discussed, a short video they had to click on in order to watch, etc. In every case, there was a required action that had to be taken. This kept discussions lively and guaranteed student focus.

- Applicability: Professor Weinstock ensured that they would find the content of the Collaborate sessions relevant by asking for specific examples of principles being discussed from their own careers. Many of his students were from Latin America or Europe so assignments and discussion questions would have them illustrate a model or theory with a real-life example from their home countries. In this way, there was constant reinforcement of the notion that the knowledge being acquired was practical and highly applicable to the real world.

- Supplementary content: Professor Weinstock made sure to include additional content (not in the textbook) in his blackboard collaborate sessions. This ensured that students saw the urgency of attending and participating actively in these sessions.

Professor Weinstock usually prepared material for a 45-minute session, planning to allot the remaining 15 minutes for Q & A. Invariably, however, one hour was not enough to complete the discussion, due to student interest and enthusiasm. Indeed, students were virtually fighting for the chance to speak up and express opinions. This is, of course, a wonderful problem to have, for it means students are truly engaged, interested in the subject matter and eager to provide feedback and participate.

When asked what he would say to a Blackboard Collaborate newcomer, Professor Weinstock noted: “don’t be concerned, but definitely be prepared.” Get familiar with the technology (there is support to help you learn how). The technology is very easy; however, you should master it before the Collaborate sessions begin. The Blackboard help desk is also available for any last-minute technical difficulties. Most importantly, he noted that like in any classroom-based course, you must plan and rehearse your material. He sees teaching somewhat like a performance on a stage and, although you are not expected to “memorize your lines” you do need to know your material, how you will transition from one topic to another and where you want to land (i.e., the conclusions you want to make). Take your students on that planned journey with you and be ready for some wonderful and unexpected detours along the way.