At a glance

It would be hard to discuss modern pedagogy without mentioning flipped learning, an approach that rethinks the traditional classroom experience by “introducing course concepts before class, allowing educators to use class time to guide each student through active, practical, innovative applications of the course principles” (Flipped Learning Global Initiative, 2019).

Who to contact

Learning Innovation and Faculty Engagement: Gemma Henderson, Renee Evans, and Aaron Royer.

Usage scenarios

The following scenarios come from the University of Miami.

Quality Enhancement Plan

The focus of the current University of Miami Quality Enhancement Plan is on promoting learning through discussion and dialogue, and, to this end, the university has identified three relevant methodologies, one of which is flipped learning. In Fall 2019, as an important initial step in this plan, several faculty members will participate in a Flipped Learning Faculty Learning Community, which will meet seven times over the course of the semester with the overarching goal of supporting participants as they integrate flipped components into one or more of their courses.

To increase student engagement and foster critical thinking and teamwork in her Psy110 course, Jennifer Britton, Associate Professor of Psychology, developed “Flipped Fridays.” Before each Friday class, she assigns prep work (e.g., text, video, questions for reflection) on Blackboard and then, during class, students engage in hands-on group activities which build on this prep work. In terms of logistics, Professor Britton assigns students to groups - which are rotated each week - and monitors group progress using color-coded cups: red for actively working, green for ready to move on to the next activity, and yellow for help needed.

College of Arts and Sciences

In the Fall 2017 ‘Flipped Learning’ issue of A&S magazine, the College of Arts and Sciences featured multiple stories of faculty engaging with flipped learning within their courses, including case studies and podcast assignments.

College of Engineering

In 2016, UM’s College of Engineering embarked on an active learning initiative as part of the strategic plan to redefine undergraduate engineering education. Flipped learning is an integral part of the initiative and was implemented as part of an active learning cycle. Flipped learning can be viewed as a gateway to active learning and so it made sense that it would be implemented this way. Several classrooms were converted to active classrooms to facilitate flipped learning and many of the faculty were trained in identifying tools, resources and teaching strategies that would help them to adopt a flipped learning approach. To learn more about this initiative please visit Transforming 21st Century Engineering Education.

This initiative also resulted in the redesign of several courses that would utilize the flipped learning approach. One of which was the freshman introduction to engineering course. The course was renamed ‘Introduction to Innovation in Engineering’ and utilized a problem-based format. There were no textbooks or exams. Students were presented with a semester long challenge and were required to come to class prepared to critically think about the problem and find a solution. To learn more about this course please visit, Students Engineer Innovation.

Cane Academy, Miller School of Medicine

In October 2014, David Green, Sr Instructional Designer in UMMSM’s Educational Development Office, led the design, development, and implementation of the “Cane Academy,” an initiative at the UM Miller School of Medicine to forge collaborative relationships with faculty members to “flip the classroom” using short instructional videos coupled with companion assessment exercises. Further discussion about the Cane Academy initiative is published on EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative (ELI) (Green, 2016).

References

- Abeysekera, Lakmal and Dawson, Phillip. (2015). Motivation and cognitive load in the flipped classroom : definition, rationale and a call for research, Higher education research & development, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 1-14.

- Akçayır, G., & Akçayır, M. (2018). The flipped classroom: A review of its advantages and challenges. Computers & Education,126, 334-345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.07.021

- Awidi, I. T., & Paynter, M. (2019). The impact of a flipped classroom approach on student learning experience. Computers & Education,128, 269-283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.09.013

- Bovill, C., Cook‐Sather, A., & Felten, P. (2011). Students as co‐creators of teaching approaches, course design, and curricula: Implications for academic developers. International Journal for Academic Development, 16(2), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2011.568690

- Flipped Learning Global Initiative (FLGI). (n.d.). Flipped Learning International Definition. Retrieved July 26, 2019, from Flipped Learning Global Initiative: The Exchange website: https://flglobal.org/international_definition/

- Green, D. (n.d.). Next-Generation Medical Education: Facilitating Student-Centered Learning Environments. Retrieved July 26, 2019, from https://library.educause.edu/resources/2016/3/next-generation-medical-education

- Gündüz, Abdullah Yasin Y., and Buket Akkoyunlu. "Student Views on the Use of Flipped Learning in Higher Education: A Pilot Study." Education and Information Technologies 24.4 (2019): 1-11. Web.

- Morrone, S., Flaming, A., Birdwell, T., Russell, J., Roman, T., & Jesse, M. (2017, December 4). Creating Active Learning Classrooms Is Not Enough: Lessons from Two Case Studies. Retrieved July 26, 2019, from https://er.educause.edu/articles/2017/12/creating-active-learning-classrooms-is-not-enough-lessons-from-two-case-studies

- O’Flaherty, J., & Phillips, C. (2015). The use of flipped classrooms in higher education: A scoping review. The Internet and Higher Education, 25, 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.02.002

- Šāhīn, M., & Kurban, C. F. (2016). The flipped approach to higher education: Designing universities for todays knowledge economies and societies. Bingley: Emerald.

- Shi, Y., Ma, Y., MacLeod, J., & Yang, H. H. (2019). College students’ cognitive learning outcomes in flipped classroom instruction: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Journal of Computers in Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-019-00142-8

- Wang, Y., Huang, X., Schunn, C. D., Zou, Y., & Ai, W. (2019). Redesigning flipped classrooms: A learning model and its effects on student perceptions. Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00366-8

Research Team

Aaron Royer: Senior Instructional Designer, Academic Technologies

Gemma Henderson: Senior Instructional Designer, Academic Technologies

Renee Evans: Senior Instructional Designer, Academic Technologies

What is it?

To begin to define flipped learning, it is useful to reflect on the word “class” - after all, flipped learning is, at its core, just another way of conceiving of a class. What happens in a class? What is the most valuable use of class time? What are the roles of the teacher and students? How is the physical space organized?

In a flipped classroom, students do traditionally in-class activities - watching lectures, for example - at home and spend class time engaged in more cognitively-challenging tasks that require them to discuss, apply, and synthesize. This leads to significant changes, not only in the structure and timing of activities, but also in the roles of the teacher and students and even in the arrangement of the physical space, which is often required to facilitate more active participation. The teacher becomes a guide in the learning process, choosing content, designing and scaffolding in-class tasks, and carrying out a robust formative-assessment cycle, while students take on a much more active role as they self regulate their learning and participate in tasks which stimulate higher-order thinking.

It is important to note that the concept of “flipping” a class is not new and is not inherently related to technology. While the term “flipped” first appeared only recently in higher education, and slightly earlier in K12 education, the simple, yet powerful idea at the heart of it - that is, the consumption of a text or lecture at home and active engagement with it in class - predates both this term and the widespread use of technology in education.

How does it work?

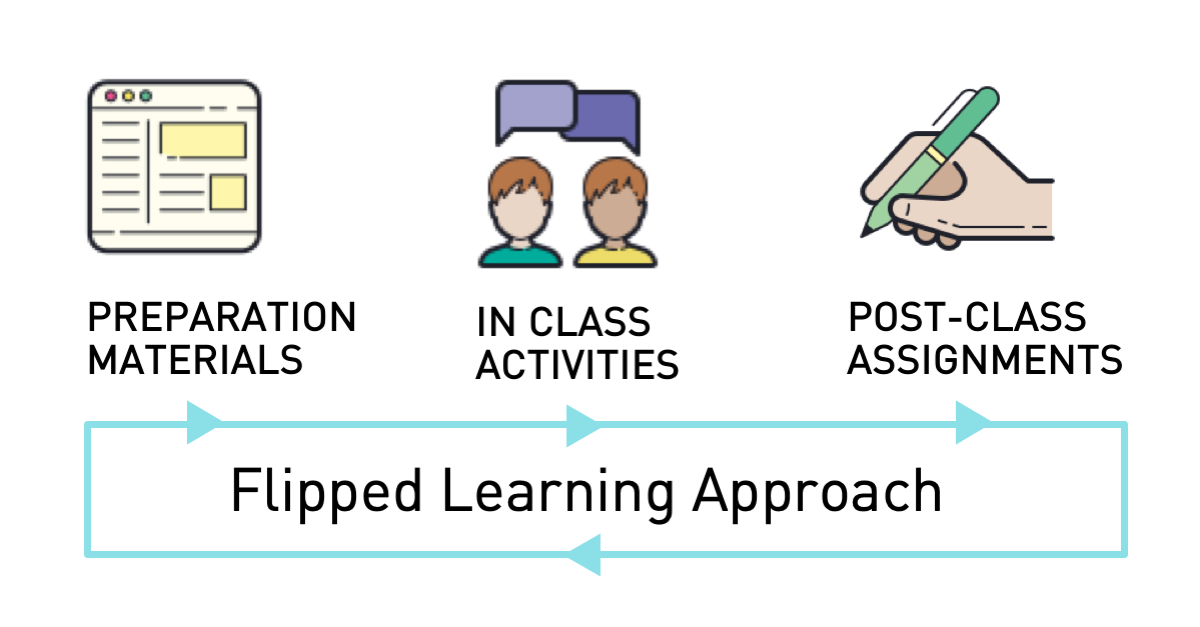

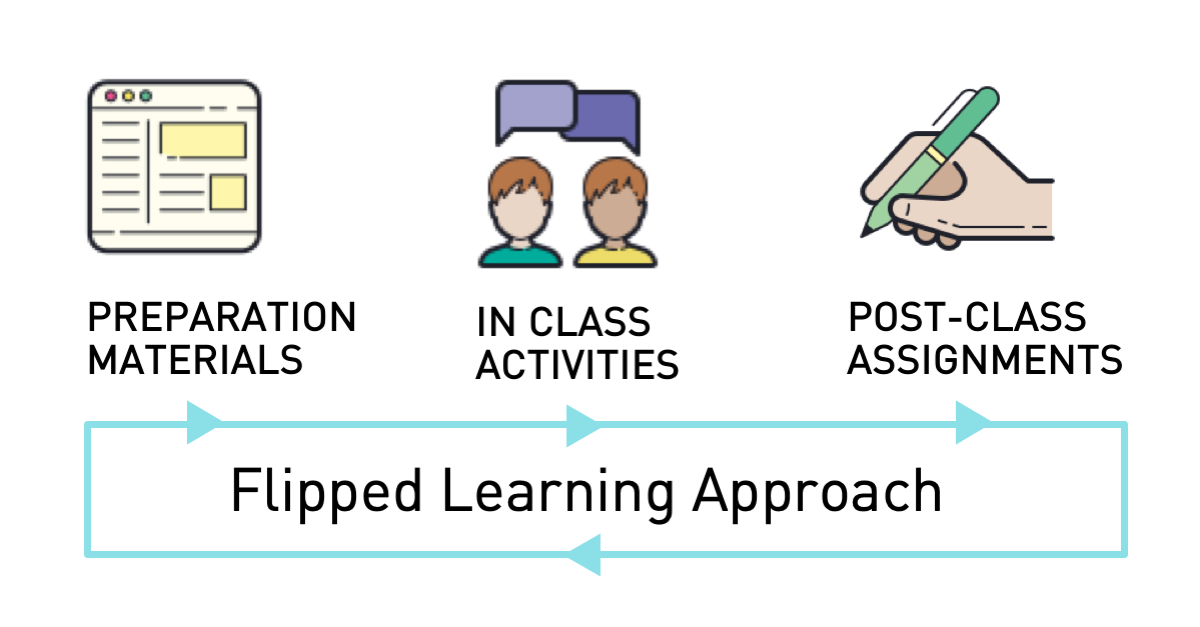

The flipped learning process involves learners engaging in materials (resources or assignments) outside of class that connect to and prepare them for engaging within a classroom session. Within a class session, learners complete in-class exercises and then complete related assignments after class before the process starts again. For an educator, flipped learning usually involves initial investment of time to assess and transform course objectives, assessments or activities. A few steps to consider in adopting a flipped learning approach within a course are outlined as follows:

Analyze motivations: An educator would first start by questioning how a flipped learning approach will relate to their goals as a teacher and or as a researcher, and what institutional resources are available to support this transition. For example, if an educator wishes to introduce field-work or lab-based undergraduate research within a course, students will need to engage with targeted resources to prepare for a class session. Resources and funding from peers, teaching and learning centers, and subject librarians to foster this change are often available for extensive curricula change.

Evaluate opportunities: Similar to creating or updating a course, taking a holistic overview of the course by reviewing the syllabus, course content, course objectives and examining student feedback can help address key opportunities to start with a flipped learning approach. There are potentially a few ways to go about this.

- Targeted approach: Target a challenging subject or concept that students have difficulty grasping. Identifying learning outcomes (knowledge, skills, behaviors, values) of what you aim for students to demonstrate at the end of their program of study may shape the direction of the course change.

- Comprehensive approach: If unsure where to start, reviewing the course on a week/topic basis about what is important to address in the classroom and outside of the classroom can help evaluate whether a flipped learning approach is more appropriate for some, or all of the course.

Implement changes: Deciding on the instruction and assessment within and outside of the classroom depends on if an entire course is modified, or only a few components. Creating a personal ‘course plan’ with milestones can help establish the development of lesson plans, curricular resources, information or assessments. While there is often a perception that creating resources (e.g. video lectures, podcasts) is necessary, educators should consider adopting third-party resources (video-channels, journal articles or case studies) or augment existing resources. A learning management system (e.g., Blackboard Learn) can be useful in presenting content outside of the classroom to students and in communicating instructions, resources and out-of-class assignments.

Set expectations: The course will begin with setting intentional and transparent expectations of the course with students. Introducing to students the ‘flipped’ modality of the class may reduce frustrations regarding the time taken to do the pre-class activities and establish their responsibility for their own learning outside of face to face contact time (O’Flaherty & Phillips, 2015). Throughout the teaching of the course, ample opportunity is spent addressing questions and discussions about out-of-class assignments, while also informally evaluating with students what is or isn’t working about this approach.

Who’s doing it?

Though implementation details vary - sometimes significantly - application of flipped principles is widespread nowadays and can be found at all levels of education and in a range of disciplines. The following are some examples, curated to illustrate this diversity of context and implementation.

Eric Mazur, PhD: In the late 90s, having become frustrated at the lack of depth in his students’ understanding of Physics concepts, Eric Mazur, Professor of physics at Harvard, started to explore alternatives to lecturing, eventually arriving at what he calls peer instruction, a method which clearly qualifies as flipped learning, but predates the term. In essence, students read texts at home and then spend class time with peers, first, striving to make sense of the key concepts in these texts and, second, engaging in tasks which require them to analyze and apply these concepts.

Robert Talbert, PhD: Another early adopter of flipped learning, Robert Talbert, Professor of Mathematics at Grand Valley State University, has written extensively about his experience with flipped classrooms. In particular, his efforts have helped shift attention to the need for a standard definition of flipped learning and for best practices for flipped instructional design (see, for example, his Guided Practice Approach).

Daniel Schwartz, PhD: Professor Schwartz, Dean of the Stanford University College of Education, teaches with what he refers to as the Double Flip, a variation rooted in the observation that assigning lectures for homework is not enough to ensure courses are engaging and student centered. Long lectures are, according to Schwartz, inherently boring. As such, he has his students engage initially with content through some sort of reflective activity and then begins class with a short discussion of this content followed by a series of student-centered activities.

Why is it significant?

In order to examine the significance of flipped learning we need to first consider who we want our students to become in order to be successful and how flipped learning can help to develop our students. According to the mission statement of the university, “we are committed to freedom of inquiry-the freedom to think, to question, to criticize, and to dissent.” In keeping with our mission, we as educators will need to develop our students to become creative thinkers, critical thinkers, problem solvers, innovators, succinct communicators and independent learners. The flipped learning model has been shown to have a positive impact on the student learning experience in this way.

Flipped learning through the use of active learning techniques such as problem-based learning and peer instruction provides opportunities for students to be engaged in activities that require higher-order thinking skills including analysis, synthesis and evaluation, thereby developing in our students the ability to think critically and solve problems.

However, simply flipping the classroom doesn’t necessarily result in learning. Faculty will need to spend significant amounts of time planning their course or class. This means carefully thinking about learning goals, the mode of presentation of content, appropriate assessment methods and teaching strategies that will engage students in meaningful ways before, during and after class.

What are the downsides?

Several potential pitfalls have been reasonably well documented in the literature and need to be considered when deciding whether flipped learning will work in a given context and, if so, how it will be implemented.

Breaking expectations: Students inevitably begin a course with an expectation - usually based on previous educational experiences - of what a “class” should be. Those used to a more teacher-centered, lecture-based class may not respond well to flipped learning, at least initially. They might not be comfortable with their new, more active role or with the teacher’s shift to “guide on the side” from “sage on the stage.” Student resistance may also be related to more concrete and specific concerns, such as a perceived lack of depth in out-of-class texts or lectures, a decrease in teacher feedback, or the absence of time for content questions (Gündüz, A.Y. & Akkoyunlu, B., 2019). Research indicates, though, that conveying clear expectations to students from the outset can help to mitigate the effects of this gap in expectations (O’Flaherty, J., & Phillips, C. 2015).

Student preparation: Flipped learning requires students to take significantly more responsibility for their learning, which, in the best case scenario, fosters autonomous learners who are capable of self regulating. However, some students are resistant to, or not prepared for, the added responsibility (O’Flaherty, J., & Phillips, C. 2015), and, as a result, don’t regularly complete homework assignments. This can lead to headaches for teachers and students alike, as in-class activities are highly dependent on homework content. However, research suggests that student engagement with pre-class activities increases when they are clearly connected to in-class activities (O’Flaherty, J., & Phillips, C. 2015).

Upfront work: Since the teacher must assume and adjust to a different role, flipped learning may, at least in the short term, bring a significant amount of extra work. In addition to transforming lectures so that they can be seen outside of class, teachers also need to rethink the types of tasks they will have students do in class, and their approach to assessment, both formative and summative. To keep the workload manageable, it is often a good idea to gradually incorporate flipped elements, as described, for example, in Robert Talbert’s One Year Plan.

Where is it going?

Faculty development and communities: Flipped learning is still going strong within educational development, practice and research. Formalization of the flipped learning community has emerged with the Flipped Learning Global Initiative (FLGI), a for-profit organization and coalition of members that provide guides, professional development, and research on flipped thinking and teaching practices. Multiple higher-education institutions (e.g. Duke University, Boston University, Princeton and Harvard) have introduced faculty development workshops, programs and incentives, focusing on flipped learning to provide faculty support in course design.

Learning spaces, interactive resources and technologies: Advancements around rethinking learning spaces, equipment and technologies have emerged and support a flipped learning approach. There has been a surge in redefining and designing ‘active’ learning spaces across higher education institutions and including those at University of Iowa, Purdue University, and Indiana University, with faculty development at the center, to support these changes (Morrone et al., 2017). Publishers continue to expand the capabilities of instructional resources, through interactive textbooks, with annotation features, 3D visualizations and multiple assessment types. Explorations beyond video-lectures outside the classroom are taking shape through 360 virtual reality video experiences or through presentation-based virtual tours.

Student-centered pedagogies: With the increasing empirical literature about the rewards of flipped learning (O’Flaherty & Phillips, 2015; Shi, Ma, MacLeod, & Yang, 2019), flipped learning invites further educator engagement with ancillary pedagogies. By focusing on the role of students in learning environments (online, or face-to-face) , approaches such as active learning, SCALE-UP pedagogy, or service-learning, recenter the student as the driving force and in control of their learning. In consequence, the adoption of student-centered pedagogical frameworks and ideas such as universal design for learning, human-centered design or design thinking has taken root into educational practice, inviting students to become co-creators of the course design process (Bovill, Cook‐Sather, & Felten, 2011).

What are the implications for teaching and learning?

Flipped learning is more demanding for both the teacher and student and may impact teaching and learning in the following ways:

Student motivation: According to Abeysekera and Dawson (2015), the success of flipped learning “relies upon students undertaking substantial out-of-class work and being motivated to do so independently” (p. 7). A lack of motivation by some students can result in failure. According to the self-determination theory, any environment that supports an individual's need to feel in control (autonomy), the ability to master knowledge, skills and behaviors (competence) and a sense of belonging (relatedness) will have a positive impact on their performance, persistence and creativity. Faculty will need to focus on creating a learning environment that develops intrinsic motivation in students by taking into consideration those three things.

Changing roles for faculty and students: In the traditional classroom, the faculty takes on the responsibility of learning for their students by being the primary source of information. In the flipped learning model, this changes and faculty will become facilitators of learning and students will be challenged to take more responsibility for their learning. As the facilitator of learning, faculty should not use the class time to transmit knowledge, but rather to engage students in discussions, hands-on activities and problem solving (Akçayır, G., & Akçayır, M. , 2018).

Rethinking teaching strategies: The goal of flipped learning is to facilitate a deeper understanding of the content and real-world applicability of knowledge, so faculty will need to think about ways they can engage their students in learning that are meaningful and challenging. Active learning is one way of doing that and flipped learning is the gateway to using active learning techniques in the classroom. Faculty will need to consider using strategies such as peer instruction, problem-based learning, case-based learning, collaborative learning, or inquiry-based learning to help students acquire the necessary knowledge and skills for the course.

Students as content creators vs. content consumers: The flipped learning model provides an opportunity for students to be content creators. For example, instead of a faculty member creating videos for a topic, students can be tasked with doing research, creating a storyboard, and recording content. The exercise of content creation can help students become better critical thinkers and problem solvers.

Learning as a continuous process: As technology advances there will be even more modalities through which faculty can provide content as well as have students create content, and there will be more ways for faculty to interact with students and provide support outside of the classroom. No longer should faculty think of their course as three separate 50 minute sessions, but rather as a 24 hour cycle.

Use of technology: Since flipped learning involves the transmission of knowledge outside of the classroom, the use of class time for engaging and interactive activities and the completion of pre and/or post class learning activities, the use of technology will be important and helpful for facilitating learning in this way. Examples of useful technology may include video-creation tools, learning management systems such as Blackboard, student response systems, e-textbooks, 3-D printing and interactive presentation tools.