What is it?

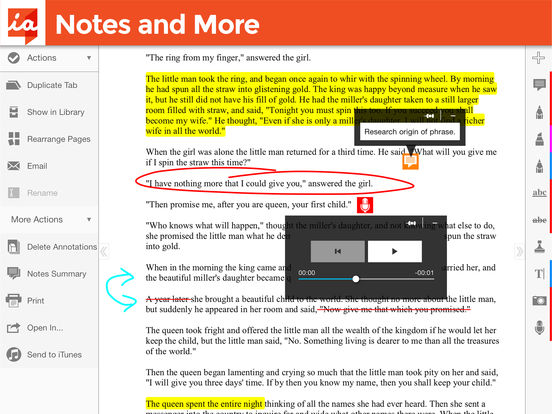

Digital annotation tools enable faculty to review electronic student submissions, directly provide personalized, detailed feedback on the assignment and support a paperless classroom. Annotation tools like Bb Annotate (Box View/Blackboard Instructor), Adobe Acrobat (Mobile/Desktop), Google Drive, iAnnotate (Mobile), allow faculty to highlight text, add comments, draw notes, and attach additional resources directly within a browser, mobile or desktop application. All tools except iAnnotate are available through the University of Miami. This Comparison of Features Table provides an overview to what each digital annotation tool offers.

How does it work?

In the context of assessment, digital annotation tools are used to communicate feedback, respond to students' work, and invite students to have an active role within the feedback process (Carless, 2016). To provide annotated feedback:

- Instructors will first need to create a preferred online location for students to submit their assignment, such as a Blackboard Assignment, Google Drive, or another cloud-based platform.

- Once assignments are collected (or downloaded) digital annotation tools facilitate different feedback approaches, instructors can add text-based comments, recommend revisions using ‘track changes,’ or clarify points by recording audio and video commentaries.

- Whether feedback is provided within the browser, mobile application or through a desktop application, instructors will submit feedback online or upload the student submission to a grading page for review.

A summarized workflow for each tool is outlined below:

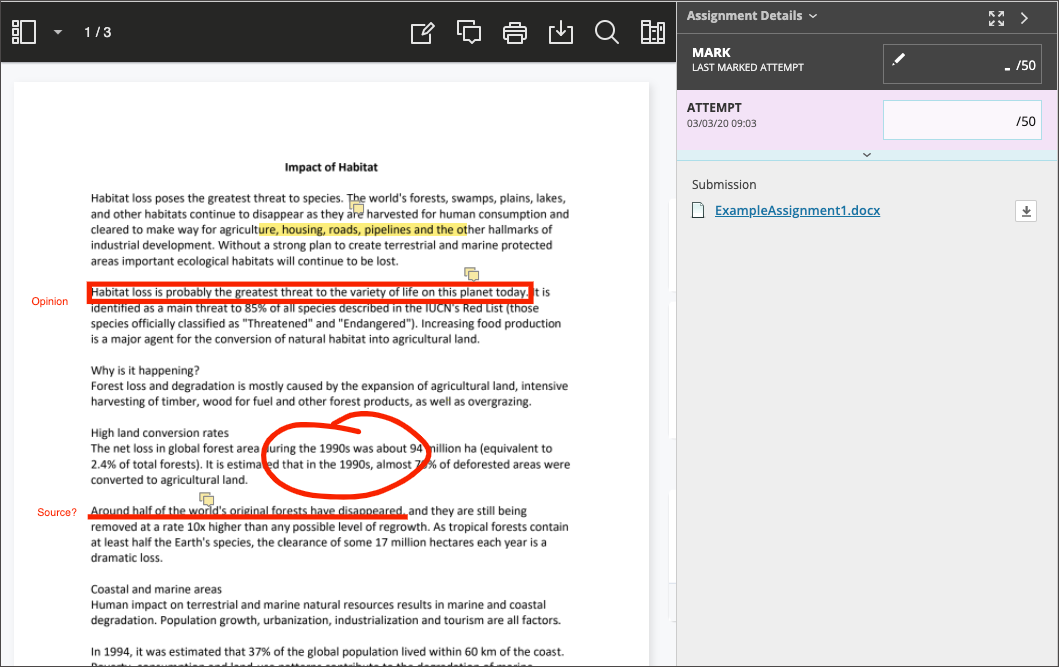

Bb Annotate: Once a Blackboard Assignment is created and students have submitted their coursework, instructors can access student submissions through the Grade Center. Bb Annotate automatically converts accepted file types into a PDF, allowing instructors to use the toolbar to add text comments, highlight text and draw annotations directly within the browser next to a grading panel. Instructors can also download student submissions, provide feedback through another application (like Adobe Acrobat or iAnnotate), add voice comments, and attach through the grading panel, before submitting final grades.

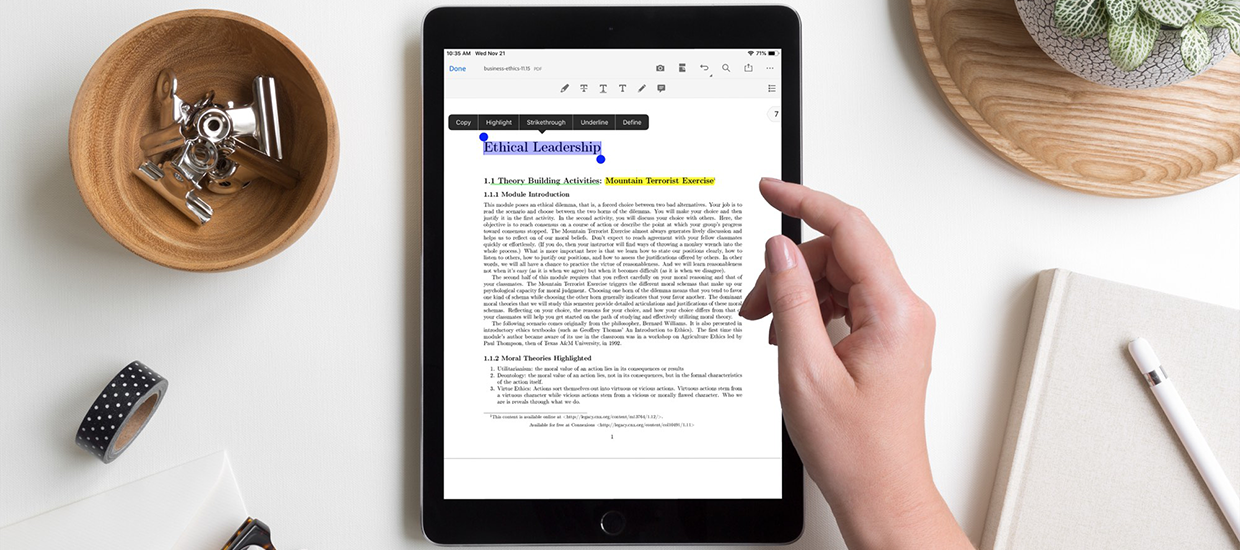

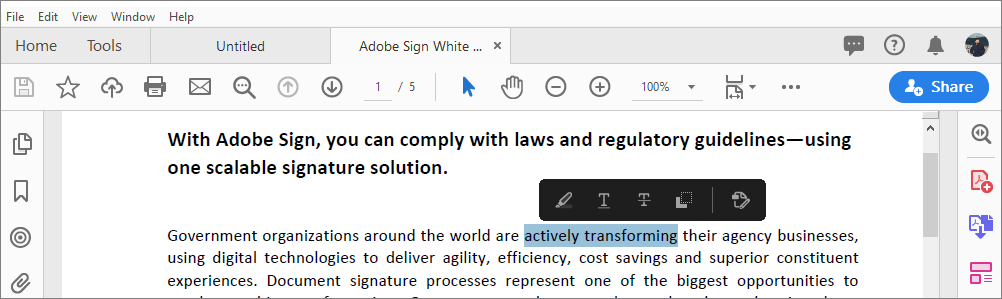

Adobe Acrobat DC and iAnnotate: To use a desktop or mobile application, and or work offline instructors would need to download submissions (individually or in bulk into a .zip file). Adobe Acrobat and iAnnotate can also directly connect to cloud solutions (Google Drive, OneDrive) to open these files and sync revisions without the need to download directly onto a device. Once a file is opened, instructors can use the toolbar to select an annotation feature and provide feedback. Final steps may include uploading and attaching the file to a grading page (e.g. within a Blackboard Assignment), or location where students will access the feedback.

Google Drive: As Google Drive is a cloud-based storage solution, some initial planning is required to consider how to collect and organize student submissions. For group-based projects, instructors may have students submit to a single group folder where students and instructors can access all submitted files and annotate directly within the browser, mobile application or through Google File Stream. For individual assignments, students may share a folder with a portfolio of work with an instructor for feedback. For a whole class, all students could submit to one ‘class folder’, but with the potential they can comment on and see each other’s work. Google Drive Add-Ons like Kaizena, allow instructors to record audio comments (only available with personal, non-UM licenses).

Who’s doing it?

Students’ use of feedback is a core factor when designing an assessment. A feedback design leveraging digital annotation tools can ensure students can learn from, understand and apply assessment feedback in future work. Sheffield Hallam University, Deakin University, Monash University and University of Melbourne leveraged digital annotation tools as part of their assessment and feedback design, particularly for formative assessments, and investigated how it can impact student learning and enable the synthesis of feedback.

- Sheffield Hallam University: Parkin et. al. (2012) explored how technology might improve student engagement with feedback by exploring three aspects of the feedback process. One part of this project focused on the submission of grades and feedback through the LMS. Students’ perspectives were positive about receiving electronic feedback, stating they would more likely revisit feedback in a typed, legible format, valued the opportunity to engage with feedback in private, and perceived the process to be faster than hard copy submission and return (Winstone and Carless, 2020).

- Deakin University: Broadbent et al., (2018) focused on a first-year psychology course that runs three times a year, with around 2100 students who take and participate in this course each year. Tutors teach and grade between 30-90 students, all leveraging shared assessment criteria and feedback practices. Students complete several assessments, including online quizzes, formative journal assignments, an in-class test and a final examination. After completing each journal assignment, students received a five-minute audio feedback response, a short written response connecting their entry to the student learning outcomes and their grade connected to rubric assessment criteria. Each feedback response also addressed the progress of the student. With the added feedback practices, student grades and student satisfaction with the feedback they received increased each year (Broadbent et al., 2018).

- Monash University and University of Melbourne: Within a large-scale cross-sectional survey at two Australian universities, 4514 students rated the importance of “detail, personalisation, and usability of various modes of feedback comments” (Ryan et al., 2019). Modes of feedback investigated included handwritten comments on an assessment, electronic annotations, face-to-face comments, audio recorded comments, video recorded comments and using a marking sheet/rubric (Ryan et al., 2019). Findings suggest that when students receive a single form of feedback, electronic annotations or digital recordings were the most suitable for offering a detailed response. Digital recordings in particular were perceived by students as effective mode for detailed and personalised feedback comments. Overall, even within the same assessment, students were suggested to benefit from receiving different modes of comments.

Why is it significant?

More Efficient: Digital annotation allows faster turnaround time right on the spot by giving comments electronically on what is being referenced, allowing conversation with one another.

Dialogic: Some digital annotation tools, like Google Docs allow instructors to post comments, instantly notify students via email so students can respond to the comments. This approach allows for the instructor and student to interact on the spot and join in on the conversation.

One space for feedback: Using digital annotation potentially saves time, as everything is in one platform. It allows for everyone to connect centrally and provide feedback in the moment, which is faster than communicating through email. Any changes or feedback that is provided can be recorded, and students can access and revisit feedback at any time.

Privacy: By using learning platforms like Blackboard, and Blackboard In-line Grading, students can receive individual and private feedback. Avoiding traditional dissemination of feedback via email prevents student work being sent to an external party accidentally.

Digital/Paperless: A paperless approach is not only environmentally friendly, but provides benefits such as documentation organization while saving time and is cost-efficient.

What are the downsides?

Instructor-led: Annotation tools potentially replicate the practice of feedback as teacher-centered, ‘telling’ answers and transmitting comments (Ryan et al., 2019; Winstone & Carless, 2020). “Feedforward” practices that focus on future development of a learner, such as connecting responses to previous and upcoming assessments, invite a dialogue between students, and help them critically reflect and improve future performance (Ball et al., 2009).

Tone of annotation: From studying handwritten annotations on essays, Ball et al. (2009) suggest that when annotating on students’ work, instructors enter a dialogue with students and would need to remain aware about the style, tone and wording used. The tone of annotations may undermine confidence and impact motivation of a learner, therefore constructive, and balanced comments (that helpfully identify areas of weakness as well as positive contributions) were recommended. Digital voice annotations can also help clarify written comments and address tone issues.

Type of digital annotation: Since effective feedback is usually specific, timely, and actionable, if tools are used to underline text without further explanation, evidence suggests this has little impact on students and improves their essay writing technique. (Ball et al., 2009). Leveraging assessment criteria, different feedback modes, using comment banks, or adding audio feedback can help contextualize feedback further.

Limited file types: While video, website and programming annotation tools do exist, most digital annotation tools primarily focus on written submissions and accept file types like word documents, some image formats, and PDF files. Other image file types and websites often require some conversion by students or instructors using tools like Adobe Acrobat DC or iAnnotate to convert to a PDF.

Time-consuming: Adding text-based annotations is a time-consuming process, particularly for large-enrollment classes or multiple cohorts of students, audio-visual responses has been shown to reduce marking time, in addition to using criteria-based rubrics (Ryan et al., 2019).

Where is it going?

Feedback is central to the learning process and particularly so in active pedagogies, where it is an important manifestation of the “guide on the side” role. Digital annotation tools can help to ensure that feedback is nuanced, timely, and frequent and have the following implications for teaching and learning:

Presence in online and hybrid courses: In online courses, and to a lesser degree in hybrid ones, instructors must be more deliberate about establishing “presence” since students have few, if any, synchronous and/or face-to-face learning experiences. Thus, one of the first and most fundamental tasks in these environments is establishing and managing this presence through a routine of frequent and timely interventions. One such intervention is feedback, and digital annotation tools can help to ensure that it is detailed, timely and frequent, as well as varied in terms of mode (audio, text, video, etc.).

Nuanced feedback: While faculty and students agree in principle about what constitutes effective feedback, they often disagree about the actual utility, fairness, and comprehensibility of a given instructor’s feedback in practice (Mulliner & Tucker, 2015). Giving detailed handwritten feedback is time consuming and often yields questionable results. Due to their integration with learning management systems, digital annotation tools help to streamline basic procedures like assignment submission and feedback sharing, allowing the instructor to focus his time almost entirely on the content of the feedback. In addition, annotation tools like link sharing, voice dictation, audio commenting, among others, enable instructors to provide a level of nuance not possible in traditional, text-based feedback.

Multimodal: Instructors often default to text-based feedback, but research has shown that students prefer, and engage more with, audiovisual feedback (Deeley, 2018). Many instructors are partial to verbal feedback, too, as it allows them - through rephrasing, circumlocution, etc. - to convey a level of detail and clarity just not possible in written forms. Moreover, since written feedback is often devoid of tone and voice, it can potentially be misconstrued as judgmental or overly critical. Many digital annotation tools allow faculty to record audio - and sometimes even video - comments, which could make their feedback more comprehensible, constructive, and personalized.

Meeting students where they are: A significant portion of students’ learning experiences nowadays, inside and outside their formal courses, takes place in learning management systems (LMSs) or otherwise online. Since it is generally good practice to limit the number of spaces and platforms used in a course, instructors should consider using familiar platforms and their associated tools for feedback. Moreover, the multimodal nature of digital feedback more closely aligns with students’ expectations and current trends in teaching and learning.

What are the implications for teaching and learning?

More multimodal feedback: Digital feedback environments provide a wide range of tools that instructors can utilize to provide feedback to students. While many of these facilitate and enhance traditional text-based feedback, others open up the possibility of rich multimodal feedback, with features like audio commenting, screen recording, and link sharing. This variety of feedback is particularly important in online and hybrid courses where face-to-face interaction is limited, as it helps to establish a sense of instructor presence. The quality, availability, and usability of these tools is likely to continue to increase given current student preferences and expectations, as well as the rapid expansion of online courses and programs.

AI-based tools: Effective feedback is time consuming and thus difficult to give frequently and promptly. Intelligent grading platforms like Gradescope or Crowdmark help to remedy this situation by providing bundles of functionality that streamline the feedback process, allowing instructors to focus on giving more frequent, personalized feedback. Notable features include class and individual-student learning analytics; banks of common, reusable comments; response analysis and clustering; and a robust set of annotation tools. As the quality of AI algorithms continues to increase, so too will the features of these platforms - in particular, those related to response analysis and clustering.

Learning analytics: While students have a well-documented preference for feedback which is personalized, timely, and frequent, this quality of feedback has traditionally been difficult to deliver at scale (Pardo et al., 2019). However, advances in learning-analytics software and their integration with most major learning management systems have now made this more plausible. Learning-analytics software tracks students’ progress and interactions with course materials, providing a plethora of information which instructors can use as the basis for frequent dialogue - to include feedback - with students. Ultimately, this increases the sense of instructor presence and leads to a more personalized learning experience. Use of this software will continue to expand as students increasingly expect a more personalized learning experience and learning management systems continue to integrate and expand their analytics offerings.

Peer feedback: Peer feedback yields benefits for both the provider and receiver, and, with a few adaptations, many of the above-mentioned digital annotation tools can be used to facilitate it (van Popta et al., 2016). Blackboard Learn, Google Docs, Peergrade and Floop are a few of the platforms that currently support peer feedback in some form, and the options will only multiply as faculty increasingly integrate digital tools into their teaching workflows and look to peer feedback as a way to increase the frequency and robustness of feedback students receive.